But of course the essays are not only wise, detached and reflective, but also combative.

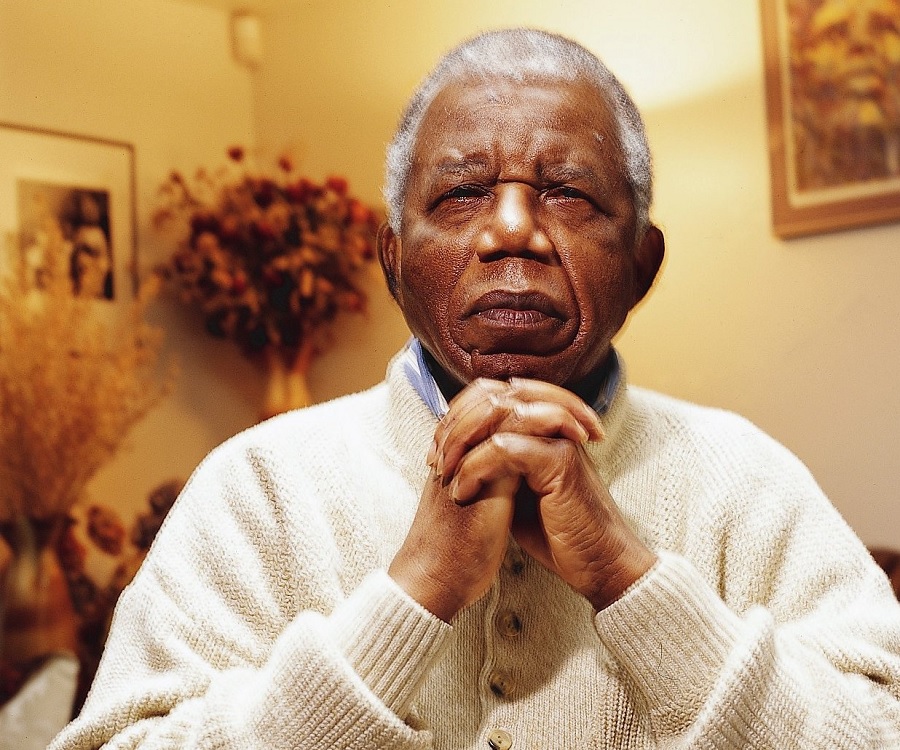

And for that, we cannot thank Trinity College, Cambridge enough. This may not be a scholarly work, but what it lacks in scholasticism, it more than makes up for in wisdom and passion, as well as those rare and often overlooked attributes of great literature, clarity and consistency of vision. In the title essay, which serves as a sort of introduction to the collection, Achebe makes it clear that this is not a scholarly work, explaining that he missed his chance to be a scholar when, 40 years ago, "Trinity College, Cambridge turned down my application to study there after I took my first degree at the new University College, Ibadan." At first this may appear to be a lowering of the readers' expectation out of modesty – but then, later, he tells us: "I am not a very modest person." And it becomes clear as one reads that Achebe is simply educating the reader on how to read these essays. And though most of them cover territories the author's followers are familiar with from other collections, such as Home and Exile, or Hopes and Impediments, it is a mark of Achebe's genius as a narrator that one could hear him many times on the same subject and never grow bored – a reminder that in the art of the storyteller, it is not content alone that matters, it is also the performance, the presentation and the passion.

They range from the author's childhood in Ogidi village in south-eastern Nigeria, to his education in Ibadan, to fame as a writer, to exile and family. They were written at different times, the earliest in 1988, the latest in 2009. As his new collection shows, this world is large and all-encompassing – his essays range from the political to the historical to the personal, yet they are all projected through an intimate, biographical lens, thus making each a milestone on his long journey on this earth. In a way this collection of essays could be viewed as a celebration of Achebe's world, and the almost 80 years he has lived in it. Achebe, on the other hand, found a ready parallel in his Igbo culture's ritual of mbari, which he describes as "a celebration, through art, of the world and of the life lived in it". Most of the participants, Achebe writes, couldn't easily make the link between literature and celebration. M any years ago, Chinua Achebe and other writers were invited to a symposium to commemorate one millennium of the city of Dublin the theme for their presentations was "Literature as celebration".

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)